Peter Smith | Homer's epic is war in all its glory and pain, scholar contends

Years after his arrival on the lethal battlefields of World War I, the English Christian author C.S. Lewis recalled his thoughts upon first hearing gunfire: "This is war. This is what Homer wrote about.

"The Iliad," the epic poem attributed to the ancient Greek poet Homer, is about war more than anything else, classics scholar Caroline Alexander told a Kentucky Center audience last week at the IdeaFestival.

And yet she grew frustrated with scholarly discussions about the work’s metrical devices, metaphors, similes, philosophical insights and clues about Bronze Age culture — anything but the brutal realities of war.

Not enough people, she said, are comparing it "to the headlines in today's newspaper."

Yet the 15,693 lines of “The Iliad” describe war with a realism that remains accessible today, despite its origins in deep antiquity.

"Of all the wars and all the war stories that have ever been told, this is the war of wars," said Alexander, author of the 2009 book, "The War That Killed Achilles."

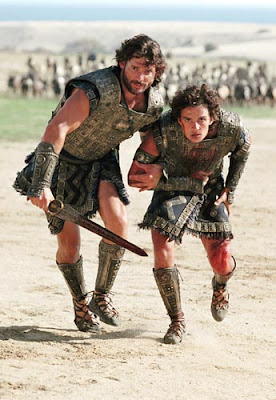

"The Iliad" — with its spectacular sweep of gods and generals, hardened warriors and vulnerable civilians, grand strategies and desperate one-on-one combat — forms part of the bedrock of Western literature and culture. It is believed to have been written nearly three millennia ago and tells about a war that took place a few centuries before that.

It covers only a couple weeks near the end of the 10-year Trojan War, in which Greek forces sailed to what would become Turkey to besiege and eventually destroy city of Troy.

The epic doesn't cover the most legendary parts of that war — such as the sneak attack from the wooden horse or the death of Achilles after being pierced in his vulnerable heel. Even the incident that started it all — the Trojan abduction of the Greek royal woman Helen, leading to the famed launch of a thousand ships to get her back — is told only in flashbacks.

Instead, the story focuses on the great yet rebellious warrior Achilles. He dares to denounce his commander-in-chief Agamemnon as incompetent for leading his exhausted, demoralized troops to useless deaths in a useless cause.

Achilles says he has no stake in the war — that Trojans had never "driven away my cattle or my horses, never … did they spoil my harvest." Alexander hears a modern echo in Muhammad Ali's statement in the 1960s that he had "no quarrel with them Viet Cong."

For centuries, Alexander said, elite schools in England and America taught "The Iliad" in part to boost the war spirit of its rising generations of leaders.

But in reality, she said "The Iliad" is a poor recruiting tool.

It does flow with talk of bravery and glory. But it also describes the piercings of spears and the cuts of swords with such clinical precision that it reads like a modern autopsy report.

(And C.S. Lewis, for all his elite Oxford credentials, wasn't fooled by any rah-rah interpretations of Homer. He noted that even Achilles told a Trojan elder that he was there "afflicting you and your children," with no mention of patriotic service. Only the majesty of Homer's poetry makes the story bearable, wrote Lewis. He quoted the German poet Goethe, who said the lesson of "The Iliad" is "that on this earth we must enact Hell.")

Homer provides the names and the personal attributes of almost all victims of the warfare, Alexander noted. More remarkably, many of these victims are Trojan, and yet the Greek audience learns enough about their enemies — and the wives, children and aging parents they leave behind — to lament their deaths.

"You understand without being instructed that this is lamentable, not glorious," Alexander said. Homer describes one slain Trojan as a "friend to all humanity."

"That's not the kind of thing (about which) any audience, Greek or Trojan, modern or ancient, would say, 'Oh great, he's dead,'" Alexander said.

One of the most poignant scenes in the entire poem comes when Hector — the Trojans' leading soldier — parts with his wife, Andromache, and their young son. The heartrending scene has been repeated right up to the present day in departure ceremonies for troops heading to war.

When Achilles does kill Hector, he drags his body around the walls of Troy as its citizens watch in horror. Alexander sees a modern parallel in the deliberate desecration of American bodies after the Battle of Mogadishu in Somalia. (Eventually, due to the pleas of Hector's mourning father, Achilles returns the body for a proper burial.)Yet to call "The Iliad" an anti-war or pacifistic treatise is too simplistic, Alexander said.

This epic is too wise for that," she said. "This epic recognizes that savage fact … that war is a necessary, tragic, apparently enduring and ineradicable part of the human condition."

And Achilles rails against the divine authors of that condition as fiercely as he rebelled against his human general. While the humans wrestle in desperate combat, the deities on Mount Olympus pull the strings of destiny, meddling in the warfare, but always returning to their blissful feasts and trysts.

"This is the fate the gods have spun for mortal men," Achilles says near the end, "that we should live in misery, but they themselves have no sorrows."

Long after Homer, many Greeks — and other Westerners they influenced — exchanged their Teflon gods for belief in a divine man of sorrows. Yet "The Iliad" endures in giving voice to human rage against war and other miseries — and in enabling empathy with those on the other side of the battle lines.

Peter Smith is the religion writer for The Courier-Journal. This column is adapted from his Faith & Works blog at www.courier-journal.com/faithblog. He can be reached at (502) 582-4469.

Comments